18 Nov Government-Published Inflation Rates vs Actual Price Increases

[Note from the author: This post was originally published in 2012 on a blog entitled “Further to Freedom.” This blog was an attempt of mine to communicate some of the complexities of economics in an accessible, easy-to-understand way. The blog was organized by ‘Levels’, which I thought would help readers to select articles which better corresponded to their level of economic understanding. I had originally envisioned this as a collaborative project and wanted to bring in a handful of others to contribute articles. That vision never materialized, but the time I committed writing and working on the project gave me a deeper understanding of the topics, and I’m still happy to share the work. This particular article was categorized ‘Level 3’.]

Every month the government publishes inflation rates that have been calculated based on that month’s Consumer Price Index, or CPI. (The CPI is based on the change in prices of a particular ‘basket of goods’, or a predetermined set of goods and services.) The inflation rate is a very important number—banks use it it determine APR’s, investors use it as a ‘market thermometer’, and it generally says quite a bit about the economy. Originally ‘inflation’ was used in reference to the money supply of a market. Inflation was literally ‘inflating’ the money supply with more dollars. This generally causes market prices to rise because the value of each unit of currency diminishes with each unit of currency added to the money supply. As the dollar becomes less valuable businesses must raise their prices to maintain their bottom line. The important feature of inflation is that it is determined by money supply, not by market prices.

Presently, however, many economists (including those who work for the federal government) have made an effort to change the definition of inflation—they argue that inflation is based on market prices instead of money supply. This is where CPI comes in. The government looks at the CPI, which has been calculated from their own basket of goods, and turns it into a percentage—there is our inflation rate! It’s almost too simple to be true. And, in fact, it is. CPI, simple as it is, offers an analyst a very broad field of information. As we all know, market prices fluctuate for myriad reasons. Holidays, natural disasters, styles and trends, new technologies, political elections, money supply—these all play into market prices. There is absolutely no way that CPI can accurately give us a proper reading on monetary inflation. Beyond the fact that CPI offers only very broad data, the final numbers are correlated only to the ‘basket of goods’ that one uses, and the government’s economists can be as selective of what goes into that basket as they desire, probably choosing prices that offer the most desirable results.

So what does this look like? Let’s consider three items which most of us are familiar with: sugar, bread, and stamps. Consider the chart below:  The inflation rates given are an average of the yearly inflation for that decade. Now, clearly this doesn’t give us the whole picture (adjusting the inflation rate to include all ten years of the decade will still yield rates less than 70%), but we begin to see that market prices are clearly increasing at a greater rate than what the government is suggesting. For any one product to double in price over the period of ten years is borderline offensive considering the progress an industry makes in efficiency and technology, which should drive prices down, not up.

The inflation rates given are an average of the yearly inflation for that decade. Now, clearly this doesn’t give us the whole picture (adjusting the inflation rate to include all ten years of the decade will still yield rates less than 70%), but we begin to see that market prices are clearly increasing at a greater rate than what the government is suggesting. For any one product to double in price over the period of ten years is borderline offensive considering the progress an industry makes in efficiency and technology, which should drive prices down, not up.

So let’s look at some actual prices. US Postal stamps are supposed to closely follow the rate of inflation. The Postal Service is allowed to increase prices only in relation to the published inflation rate, so perhaps there will be little difference:

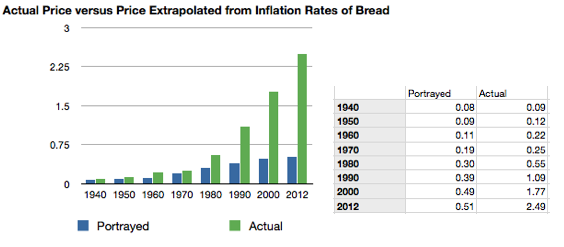

We see that the price of stamps is, in fact, much more appropriate to the rate of inflation. In some cases the difference is almost negligible—$.03, $.01, etc.. But what about products that don’t change based on ‘published inflation rates’, but change based on actual market pressures and trends? Consider bread, one of the most common household grocery purchases:

We see that the price of stamps is, in fact, much more appropriate to the rate of inflation. In some cases the difference is almost negligible—$.03, $.01, etc.. But what about products that don’t change based on ‘published inflation rates’, but change based on actual market pressures and trends? Consider bread, one of the most common household grocery purchases:

Here we find an enormous difference in the actual price of bread versus what the published inflation rate would have us believe. What about the production of a loaf of bread has changed? Have the ingredients changed? Are the loafs bigger? Perhaps the packaging is more costly? I suggest two main factors in the increased price: an inflated money supply and excessive government regulations. Consider the amount of licenses, fees, employee taxes, benefits, code compliances, etc. that a company must now consider when producing a single loaf of bread. The costs are astronomical! But these internal business requirements cannot account for a 2766% increase in cost. The answer must be found in what might be considered ‘real’ currency inflation. Since 1933 the US dollar has lost 94% of its value. Inflation from 1933 to the present has been 1679%—this means that an item costing $10 in 1933 would cost $177.94 in 2012. Surely it is not so much more costly to produce a loaf of bread in 2012 than it was in 1933. There is some real, unhealthy manipulation of currency at work here, and it cannot continue like this for too long.

Here we find an enormous difference in the actual price of bread versus what the published inflation rate would have us believe. What about the production of a loaf of bread has changed? Have the ingredients changed? Are the loafs bigger? Perhaps the packaging is more costly? I suggest two main factors in the increased price: an inflated money supply and excessive government regulations. Consider the amount of licenses, fees, employee taxes, benefits, code compliances, etc. that a company must now consider when producing a single loaf of bread. The costs are astronomical! But these internal business requirements cannot account for a 2766% increase in cost. The answer must be found in what might be considered ‘real’ currency inflation. Since 1933 the US dollar has lost 94% of its value. Inflation from 1933 to the present has been 1679%—this means that an item costing $10 in 1933 would cost $177.94 in 2012. Surely it is not so much more costly to produce a loaf of bread in 2012 than it was in 1933. There is some real, unhealthy manipulation of currency at work here, and it cannot continue like this for too long.

No Comments