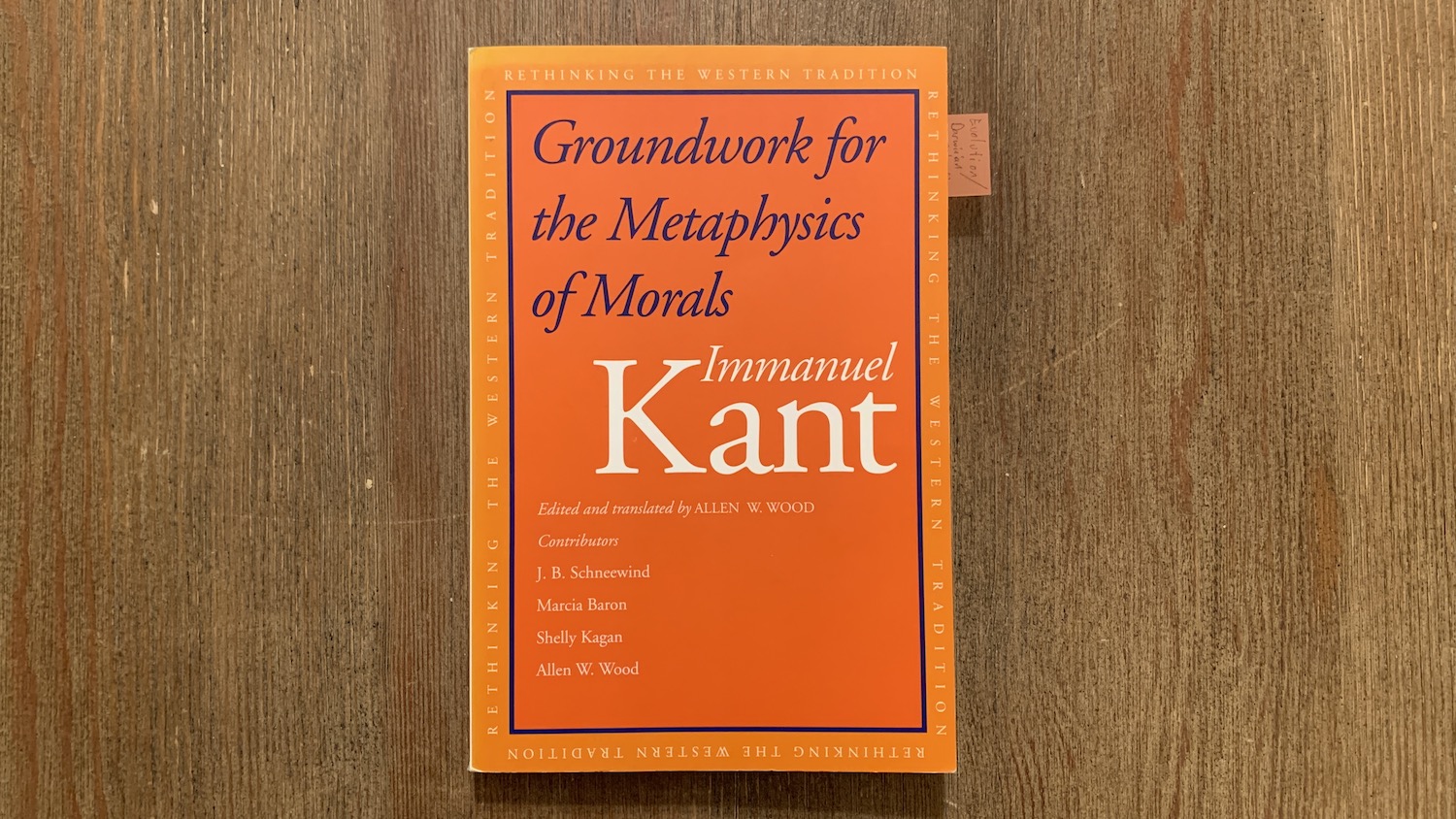

23 Nov Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals by Immanuel Kant | My Underlines

Immanuel Kant’s work here represents his most read and most influential philosophical writing. Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals is often considered the seminal philosophy book of modern philosophy, and whether or not it is still relevant in the current world, it is universally recognized as significant in the history of philosophy.

The book is short–less than 100 pages–but dense. Very dense. One of Kant’s modus operandi is his naming and formulation of specific terms, ascribing new or more robust definitions to specific words in a way that communicates his philosophy. This turns reading into a form of mental exercise. Each time one of his vocabulary words is used–words like, duty, legislative, will, worth–the reader must recall the full meaning which Kant is assigning it. This is technical philosophical writing, and so it requires that the reader approach it differently than the typical piece of non-fiction.

Because of the density of the book, reading a few essays on Kant’s book is very helpful if not required for comprehension. (Luckily, the version I read from has some of the most important essays included in the text.)

This was my second read-through of Groundwork (first was ~2010). I revisited it for two reasons: I felt I had forgotten or never really understood the core tenets of his philosophy and I really wanted to test my comprehension faculty.

If you’re a university student or just generally interested in philosophy, I highly recommend working through this book. I’ve always considered reading primary sources in their original format as a ‘must’ when it comes to studying philosophy (as opposed to reading in a textbook or ‘abridged reader’), and this is one of the ‘important ones’.

I may not have learned something that will directly impact my life, but I’ve walked away with a better understanding of the modern philosophical landscape, and that’s really what I was looking for.

Underlines

[My favorite quotes are emboldened and indented.]

All rational cognition is either material, and considers some object, or formal, and concerns itself merely with the form of the understanding and of reason itself and the universal rules of thinking in general, without distinction among objects. Ak 4:387

Where labors are not so distinguished and divided, where each is a jack-of-all-trades, there the trades still remain in the greatest barbarism. Ak 4:388

I limit the proposed question only to this: whether one is not of the opinion that it is of the utmost necessity to work out once a pure moral philosophy which is fully cleansed of everything that might be in any way empirical and belong to anthropology; for that there must be such is self-evident from the common idea of duty and of moral laws. Ak 4:389

For as to what is to be morally good, it is not enough that it conform to the moral law, but it must also happen for the sake of this law; otherwise, that conformity is only contingent and precarious… Ak 4:390

For the metaphysics of morals is to investigate the idea and principles of a possible pure will, and not the actions and conditions of human volition in general, which are for the most part drawn from psychology. Ak 4:390

The present groundwork is, however, nothing more than the search for and establishment of the supreme principle of morality, which already constitutes an enterprise whole in its aim and to be separated from every other moral investigation. Ak 4:390

The good will is good not through what it effects or accomplishes, not through its efficacy for attaining any intended end, but only through its willing, I.e., good in itself, and considered for itself, without comparison, it is to be estimated far higher than anything that could be brought about by it in favor of any inclination, or indeed, if you prefer, of the sum of all inclinations. Ak 4:394

Now if, in a being that has reason and a will, its preservation, its welfare–in a word, its happiness–were the real end of nature, then nature would have hit on a very bad arrangement in appointing reason in this creature to accomplish the aim. Ak 4:395

For since reason is not sufficiently effective in guiding the will safely in regard to its objects and the satisfaction of all our needs … Ak 4:396

It is indeed in conformity with duty that the merchant should not overcharge his inexperienced customers, and where there is much commercial traffic, the prudent merchant also does not do this, but rather holds a firm general price for everyone, so that a child buys just as cheaply from him as anyone else. Thus one is honestly served; yet that is by no means sufficient for us to believe that the merchant has proceeded thus from duty and from principles of honesty; his advantage required it; but here it is not to be assumed that besides this, he was also supposed to have an immediate inclination toward the customers, so that out of love, as it were, he gave no one an advantage over another in his prices. Thus the action was done neither from duty nor from immediate inclination, but merely from a self-serving aim. Ak 4:397

But the often anxious care that the greatest part of humankind takes for its sake still has no inner worth, and its maxim has no moral content. Ak 4:398

To secure one’s own happiness is a duty (at least indirectly), for the lack of contentment with one’s condition, in a crowd of many sorrows and amid unsatisfied needs, can easily become a great temptation to the violation of duties. Ak 4:399

For love as inclination cannot be commended; but beneficence solely from duty, even when no inclination at all drives us to it, or even when natural and invincible disinclination resists, is practical and not pathological love, which lies in the will and not in the propensity of feeling, in the principles of action and not in melting sympathy; but the former alone can be commanded. Ak 4:399

Authentically, respect is the representation of a worth that infringes on my self-love. Ak 4:401

Here, one cannot regard without admiration the way the practical faculty of judgement is so far ahead of the theoretical in the common human understanding. Ak 4:404

There is something splendid about innocence, but it is in turn very bad that it cannot be protected very well and is easily seduced. Ak 4:405

Because when we are talking about moral worth, it does not depend on the actions, which one sees, but on the inner principles, which one does not see. Ak 4:407

Pure honesty in friendship can no less be demanded of every human being, even if up to now there may not have been a single honest friend, because this duty, as duty in general, lies prior to all experience in the idea of a reason determining the will through a priori grounds. Ak 4:408

But where do we get the concept of God as the highest good? Solely from the idea that reason projects a priori of moral perfection and connects inseparably with the concept of a free will. Ak 4:409

The will is a faculty of choosing only that which reason, independent of inclination, recognizes as practically necessary, I.e., as good. Ak 4:412

The precepts for the physician, how to make his patient healthy in a well-grounded way, and for the poisoner, how to kill him with certainty, are to this extent of equal worth, since each serves to effect its aim perfectly. Ak 4:415

Thus one cannot act in accordance with determinate principles in order to be happy, but only in accordance with empirical counsels, e.g., of diet, frugality, politeness, restraint, etc., of which experience teaches that they most promote welfare on the average. Ak 4:418

The categorical imperative is thus only a single one, and specifically this: Act only in accordance with that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it become a universal law. Ak 4:421

Now I say that the human being, and in general every rational being, exists as end in itself, not merely as means to the discretionary use of this or that will, but in all its actions, those directed toward itself as well as those directed toward other rational beings, it must always at the same time be considered as an end. Ak 4:428

Rational nature exists as end in itself. Ak 4:429

…In regard to the contingent (meritorious) duty toward oneself, it is not enough that the action does not conflict with humanity in our person as end in itself; it most also harmonize with it. Ak 4:430

Thus morality and humanity, insofar as it is capable of morality, is that alone which has dignity. Skill and industry in labor have a market price; wit, lively imagination, and moods have an affective price; by contrast, fidelity in promising, benevolence from principle (not from instinct) have an inner worth. Ak 4:435

Empirical principles are everywhere unsuited to having moral laws grounded on them. Ak 4:442

Freedom must be presupposed as a quality of the will of all rational beings. Ak 4:447

Hence freedom is only an idea of reason, whose objective reality is doubtful in itself. Ak 4:455

No Comments